‘Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned; they therefore do as they like.’ – Edward Thurlow, 1st Baron Thurlow.

The veterinary professional has always attracted people who were caring, who loved animals and who wanted to ‘make a difference’. Given that they are fulfilling a vocation it is both surprising not to mention worrying that a high percentage of vets suffer from mental health issues and, tragically, are between two and three more times likely to take their own lives. Why do our vets struggle with stress, anxiety and depression? There are plenty of theories including: the long working hours, financial pressure, bearing witness to distress and the requirement to participate in euthanasia. All these factors may, indeed, play a part, but for me the real issue is ‘McDonaldization’. What is McDonaldization? The concept was popularized by sociologist George Ritzer, who used the fast-food chain McDonald’s as a metaphor to describe the homogenization and standardization of processes and products in various domains of society. McDonaldization emphasizes efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control, often leading to adverse consequences.

McDonaldization, in my view, subsumes and/or engenders several other processes as “sequelae” or “comorbidities” as follows:

- Corporatisation and Bureaucratisation. The transformation of a business or organisation into large complex organisations with many levels of abstraction between the clinical provider and our source of authority or guidance.

- The use of environment and policies to control an enterprise in ways that are beneficial to the corporation.

- The process of a company growing by acquiring diverse businesses or subsidiaries in various industries.

- When companies grow by merging with or acquiring other businesses, reducing competition in the process.

- When a company grows so large that it dominates its market, often reducing competition significantly.

- The expansion of a company’s operations, influence, and presence across the globe.

- The broad process of growing through increasing operations, markets, or product offerings.

- Automation and routinization. A computer programme or algorithm replaces and/or can overrule professional judgment.

McDonaldization promises convenience, uniformity, and efficiency, but often delivers a system that can be overly standardised, impersonal, and focused on quantity over quality. Workers may feel a loss of autonomy, and customers may experience a more automated or impersonal service. Control mechanisms reduce flexibility and creativity, both for employees and consumers.

So, to what extent does McDonaldization impact veterinary medicine?

Historically, independent practices have dominated the veterinary sector. They still represent a significant portion of total number of practices, though corporate consolidation has been rapidly increasing. Over the past decade, private equity firms have launched large-scale “roll ups” within the veterinary care industry, buying small veterinary practices and consolidating them under the ownership of larger corporations. In the USA alone between 2017 to 2023, private equity firms spent over $51 billion on merger and acquisition deals in the veterinary sector. It is the same story all over the Western World.

Not surprisingly, corporate veterinary practices generate a disproportionately high share of expenditure compared to their share of the market. Why? Higher pricing and bundled service offerings. Average expenditure at independent practices is usually lower than chain practices for basic services such as wellness exams, vaccinations, and routine diagnostics. Their pricing tends to be more variable, often tailored to the local community or individual client needs. In plain English, an independent owner can ‘cut you a break’ if they wish. Emphasis is placed on personalised care and long-term client relationships, which may result in more conservative recommendations for diagnostics or treatments.

At franchise or chain practices, average expenditure is typically higher due to standardised pricing models, programmed upselling of additional services, and use of advanced diagnostics. Some tasks are relegated to low paid employees. However, chains typically include additional fees due to corporate overhead, including a portion for investors and multiple layers of management. They often emphasise comprehensive care plans or bundled services that include additional diagnostics or wellness plans.

McDonaldization also usually reduces the geographic number, competition, and diversity of veterinary practices, especially in rural and working class urban areas. Indeed, not only may all practices in given area be owned by a particular chain; but there may be chain clinics of different brands owned by the same private equity conglomerate.

From my own long experience, I believe a substantial portion of the profession’s malaise stems from its transition over time from being an independent, labour-intensive, artisanal venture to a hierarchical, capital-intensive business. This transformation has been driven by various long-term external forces, with ‘McDonaldization’ being particularly influential.

Key stakeholders in animal care have historically been the veterinarian, the animal patient and the client; sometimes involving competitive interests. McDonaldization injects into this picture an additional complex and often stressful element in the form of a remote hierarchical bureaucratic superstructure with great power and interests that are contrary to any of the three. It subverts our professional independence and pride. It thwarts our desire to be entrepreneurial business owners.

Now let me share my experience working at a corporate franchise practice. To begin with, it was an excellent place to work in many respects. The clinic was well-equipped, conveniently located, and offered higher pay than I had received at other practices. So, what was the problem? In a nutshell, the practice operated under a rigid corporate algorithm dictated by the equity ownership, which limited my professional autonomy.

At this clinic, the standard procedure was for a technician to examine the patient and gather the client’s history. This information was reviewed by the practice manager, who would then generate a list of recommendations for me before I even met the patient. Although I was ostensibly free to treat patients and clients as I deemed appropriate, this system clearly sought to impose a standardised practice management plan.

One example of this ‘guidance’ involved treating a common condition known as a ‘hotspot’. Typically, a dog will excessively bite or lick an irritated area, as if it is burning. In most cases, this can be effectively managed by shaving the affected area, cleansing it, administering a one-time corticosteroid and antibiotic injection, and advising the client to apply a topical medication along with an over-the-counter antihistamine. This straightforward approach usually provides rapid relief, breaks the vicious cycle of biting and licking and itching; and thus allows for healing. However, at the corporate practice, the protocol required a complete blood count (CBC) and blood chemistry tests before administering any corticosteroid injection. Furthermore, the corporate management ‘strongly advised’ prescribing a broad-spectrum oral antibiotic and a cytokine modulator.

This ‘approved’ method not only inflated the client’s expense, but also increased the risk of side effects.

McDonaldization – consolidation and concentration of veterinary practices and hospitals by large equity investors – in place of independent ownership of the practice subverts a vet’s independent professional judgment, complicates their ability to balance ethical conflicts and impedes their aspirations towards ownership. Without effort to counter McDonaldization, our society’s most cherished and defining values including care for the individual and meaningful patient provider relationships are threatened.

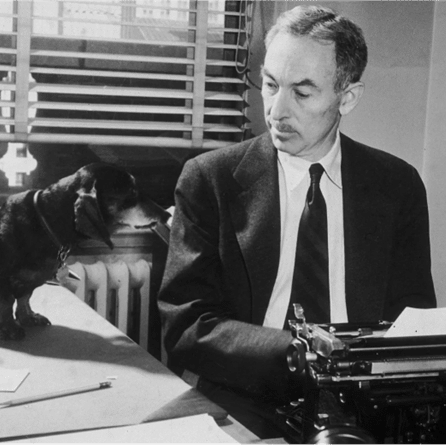

Dr. Stephen Dubin, V.M.D., Ph.D. is Clinical Professor Emeritus, Biomedical Engineering and Science, Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA