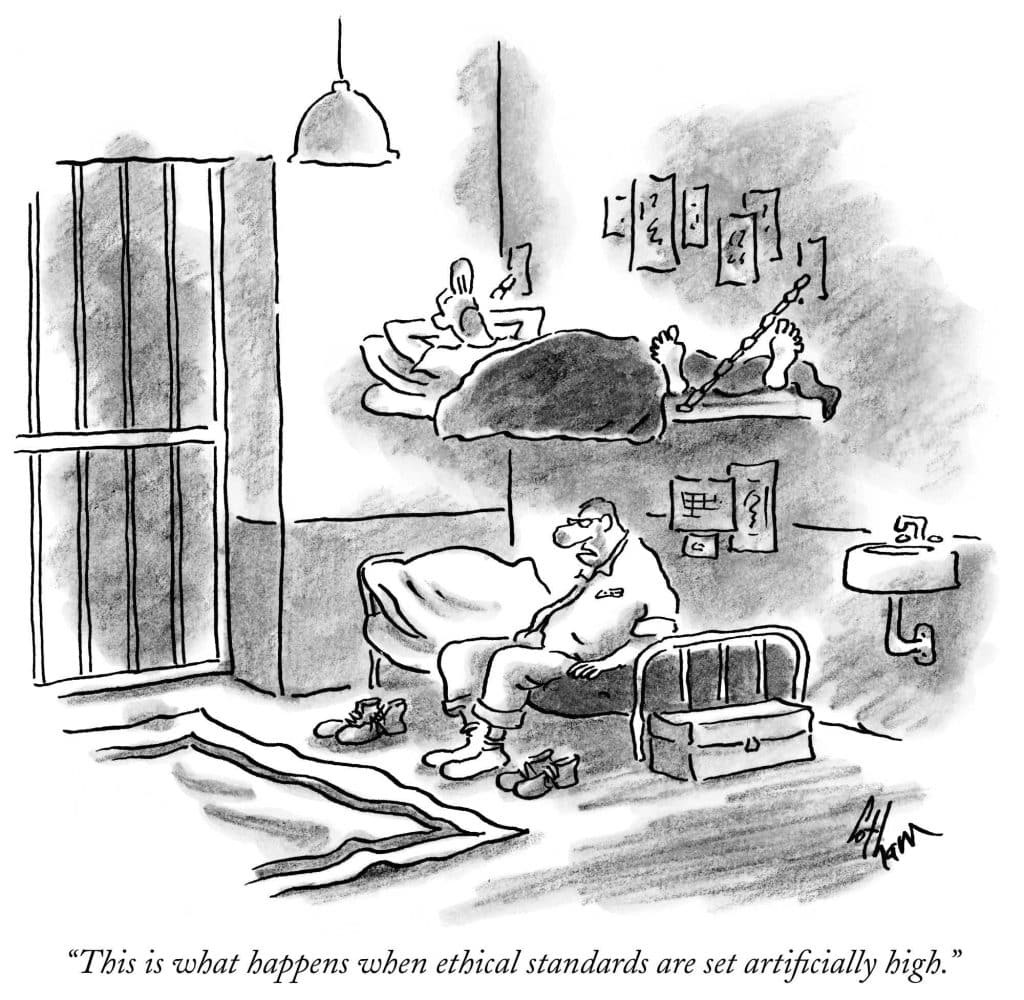

This article was submitted to us by a highly qualified Honey’s customer who has asked to remain anonymous.

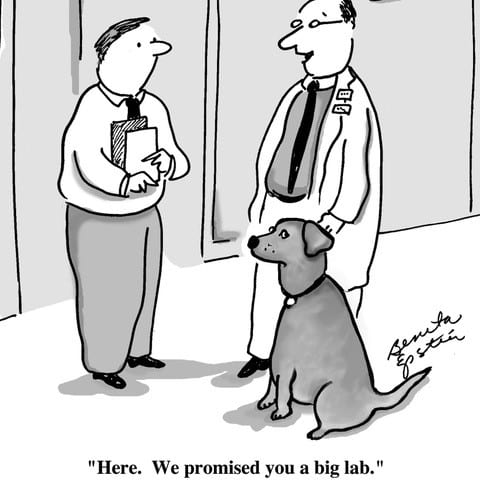

News stories appeared in July 2024 that Britain had become the first country in Europe to approve sales of lab grown meat for use in pet foods. The manufacturer has been given regulatory approval by DEFRA, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) and the Animal and Plant Health Agency (Apha) to develop and sell products cultivated from chicken cells, as food for dogs and cats.

The media reports were disquieting, partly because cultivated meat products are the very antithesis of the Honey’s ethos and partly because further investigation into the story behind the headlines raises more questions than the synthetic meat industry’s publicly available information can answer.

To understand how the idea originated, we need to begin with the history of cellular agriculture. The first serious research occurred during the 1960s and 1970s by scientists collaborating with NASA – the objective being to create food for astronauts during space missions. Having said this, the first experiments of keeping living cell tissue alive were first explored as early as 1913 (by French surgeon and biologist, Alexis Carrel). Anyway, from the 1960s onwards an increasing amount of research was being undertaken.

However, it wasn’t until the 1990s that the Food and Drug Administration in the USA approved the commercial production of in Vitro derived meat products. Then, in 2004, a company called New Harvest was founded in the USA, to raise awareness of cellular agriculture and its potential. Google co-founder Sergey Brin was an early financial supporter. The world’s first lab-grown burger was developed by a scientist at Maastricht University in 2009 and in 2013 the first actual product was launched – and eaten – at a press conference in London. Nowadays, there are dozens if not hundreds of companies and government programmes worldwide developing products for commercial use and sale.

The basic ingredients of a synthetic meat product start with the extraction of animal stem cells which are grown in bioreactors in a ‘culture media’ – a substance that enables the cells to multiply. Throughout the development process, the culture media is changed to produce muscle, fat and connective tissue. At this stage, scientists can separate the cells to create different types and shapes of ‘meat’ – steaks, mincemeat, nuggets and so forth – using a ‘scaffold’, a substance that holds the cells together and contains nutrients. As the ensuing product is tasteless and colourless flavouring and colouring is added.

So, why would anyone feed their pet a substance created in a lab, made from cells taken (in the case of the approval for pet food) from an egg and then grown in a lab container, rather than food from naturally reared animals? According to the claims being made by some producers: ‘Pet parents are crying out for a better way to feed their cats and dogs meat.’ But what constitutes ‘better’? The reasons proposed by the industry, as to why people would want to feed its products to their pets, make for interesting reading.

From an animal welfare perspective, it is certainly true that – apart from the original animals’ cells – no animals are harmed in the manufacture of this food. This is almost certainly the strongest argument in favour of lab grown meat. However, whilst it may be an alternative to intensively reared (aka factory farmed) meat it certainly isn’t going to replace it any time soon and it is doing nothing for the billions of animals that are currently suffering. The agrifood sector is badly broken and the fix is only going to come when consumers and government force change.

Another main argument that the lab grown meat industry is keen to promote is that their products are less environmentally damaging. But is lab-grown meat more sustainable? The messages regarding sustainability appear at odds with the research. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), for example, has concluded: ‘Whether cultivated meat is better for the environment is still not entirely clear due to the amount of energy used by the reactors and the processes by which cells are grown into a meat product.’ The US Government’s National Institute of Health (NIH) states that the energy used for cultured meat could be higher: ‘Due to the replacement of some biological functions, by technological processes.’ The University of California has concluded that cultivated meat is: ‘Likely worse for the climate than retail beef.’

Online information emphasises frequently that this type of product is safe and indeed, according to one producer’s website, its product has undergone rigorous testing with APHA, including for bacteria and viruses, establishing that it is free from antibiotics, heavy metals and other potentially harmful elements. However, in the same report published by the FSA (2022/3), entitled ‘Identification of hazards in meat products manufactured from cultured animal cells’, several areas of concern are highlighted, stating further research and data is needed to fully understand the potential risks or hazards of such products and that data is missing, for example, to show how cultivated meat products compare to the actual meat products they may replace.

Another potential hazard concerns the nutritional profile of cultivated products which, according to the report, could be different from meat, because: ‘The meat produced in a bioreactor will not be directly identical to meat grown in an animal.’ This indicates that whether lab-grown meat is safe to eat, might only really be proven in future, once it has entered the food chain.

One producer proudly states that its products are free from GMOs and that the company never uses antibiotics. However, it would be reassuring to know from which farms the eggs (for cell extraction) were originally sourced and how those hens were reared; while the pet-food producer may not use antibiotics, transparency is needed to ascertain if antibiotics were given to the flocks from which the cells originated.

The terminology used by the industry is often emotive. It markets the products (i.e., not just for pet food) as ‘clean’ meat – inferring that most meat currently in the food system, including organic, pasture fed, wild and so forth is unclean.

Back to how artificial meat is produced. Let’s take chicken as an example. Sample stem cells are removed from a fertilised chicken egg and then tested for resilience, taste, and the ability to divide and create more cells. The best cells are then submerged in a massive stainless-steel vat of nutrient-rich broth containing all the ingredients they need to grow and divide. After a few weeks, the cells begin to adhere to one another and produce enough protein to ‘harvest’. The result is then processed (formed, coloured, heated, etc.) to look like ‘real’ meat.

What’s wrong with this? Well, the cultured cells used to ‘grow’ the meat could easily carry an infection or mutation. Obviously, cultured cells don’t have the protection of the immune system and wider body to keep them healthy. Also antibiotics maybe employed to counter this risk. Anyway, other enemies can lurk in cells. Cancer, for example. Eating mutant misfolded proteins (prions) can also cause diseases such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (aka mad cow disease) and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. There is also the issue of what you feed the cells, because they certainly aren’t ‘eating’ real food. It takes a lot of medical-grade glucose (sugar), metabolic precursors and growth hormones to keep these cells happy. And surely, in the same way that some real meat can be deficient in vitamins and minerals, so can some (maybe all?) artificial meat.

Despite its adoption in other countries and the recently regulatory green light for use in pet foods (which could go on sale this year) synthetic meat is still very new and the risks and hazards are as yet undetermined.