Mark Elliot believes that routine chemical medication of cats and dogs is clearly causing unnecessary damage to them and the environment.

Our dogs are important to us, and yet strangely we are applying ever more toxic chemicals to them in the form of pesticides and wormers. And we are doing this ever more frequently with seemingly very little concern being raised about the short or long-term effects on man, beast or the environment – each individually a concern, together a catastrophe in the making.

Many of the products used on dogs contain controversial chemicals called Neonicotinoids – in particular Imidacloprid. It has been estimated that just one application of this chemical to treat a Labrador contains enough toxin to kill 60 million bees! The impact of many of the other chemicals is perhaps less well known, but the understanding of the damage the accumulation of so many in the environment is growing and the effects are all around us.

A report by BUGLIFE on Neonicotinoid Insecticides in British Freshwaters specifically implicated veterinary topical applications and flea collars as the most likely source of pollution in some catchment areas. Imidacloprid is highly toxic on an acute basis to aquatic invertebrates. Neonicotinoids are persistent, stable and long-lasting in the environment. BUGLIFE recommended their use should immediately be suspended in the UK and yet their call has been ignored for years now.

To honeybees Imidacloprid is perhaps the most toxic chemical ever invented. At sub-lethal levels it increases honey bee susceptibility to disease, causes significant loss in the number of queens produced, and doubles the number of bees who failed to return from food foraging trips. It is also highly toxic to some bird species including the house sparrow. Where are they now? Birds exposed to these chemicals become disorientated, lose their sense of direction, become unable to migrate and so can only decline.

The UK Veterinary Medicines Directorate recently published an open call for research into the problems, and the Veterinary Record highlighted that “the process for authorising these products may not have taken into account their environmental impacts”.

In Norway and Denmark vets don’t routinely worm dogs other than pups and nursing bitches, as it is accepted there is no need. Prescriptions for pesticides must follow a positive diagnosis of infection and there is greater awareness of environmental concerns from use of these products, as well as the human health risks. Are our parasite problems so different to those countries? No.

Yet in the UK we are told we must encourage regular worming of adult pets for roundworms and tapeworms due to the risks to pet and human health. This is just not a sustainable or even an evidence-based argument.

Worming only treats the current infestation. After just a few days new infestations establish as the eggs and infective forms of these parasites are pretty much endemic in the environment. Within only a few weeks of worming eggs are again being shed. For all the worming of cats and dogs done it is reported that 34 million toxacara eggs are released per square kilometre per day in UK.

An example of where the human health argument fails is linking dog ownership with exposure to the dog roundworm and the risk of its causing blindness in children. A very large study in Ireland failed to show the link. Personal hygiene was shown as the way forward as toxacara eggs only become infective in the external environment and contaminated food/pica/infected water sources are actually the main routes to human infection.

With ticks the main concern is Lyme disease. But dogs don’t give people the disease – that will only happen if the owner is bitten by an infected tick – and there are plenty of precautions we can take against that.

Products marketed on exploiting fears often come unstuck when facts are interrogated. Consider Canine Lungworm. Despite marketing that seeks to strike fear into our hearts that many dogs are dying a terrible death, and the only solution is to smother them in chemicals, infection is currently uncommon. Reportedly around 24 dogs die annually of lungworm, compared to nearly 100,000 that are run over. Training and buying a collar could be far better investments than a pack of toxic chemicals with all the risks they bring!

Anyway, the main source of lungworm spread is the urban fox. Data shows infection rates of foxes at around 18 per cent (50 per cent in the southeast). Without resolving this problem, we cannot hope to counter the disease.

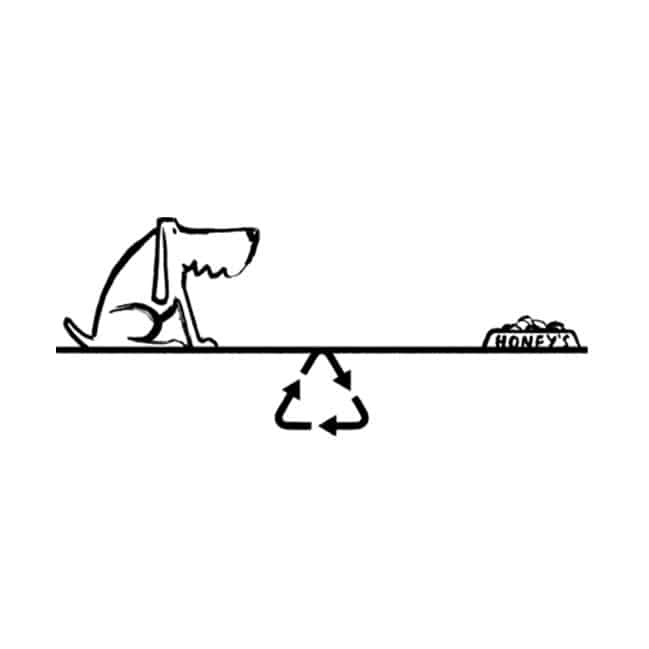

In my opinion, just regularly monitor your pet for infection with faeces sampling, and for ticks and fleas use close observation. There are some very good companies that will check the faeces for you. Only treat when necessary.

For ticks, in a high-risk area use the very effective collars that act both as insecticide and repellent but take these off on walks where the dog may go into water.

There is growing concern over the impact these chemicals applied to pets may have on human health.

Human risks from pet parasites are arguably manageable by good personal hygiene. Human risks and risks for the environment from chemicals are best managed by using them only when absolutely necessary.

For a more detailed parallel article – Peticide – see https://chichester-vets.co.uk/peticide/

About the author

After qualifying from Bristol University Veterinary School in 1989, Mark was lucky to join a practice where treatment was provided for a wide range of species, and many alternative therapies were used regularly alongside more conventional medicine. Having always wanted to be a Homeopathic Vet he embarked upon an intensive period of study at the Faculty of Homeopathy in London and achieved his qualification in this field in 1996. Mark has written six small books on Homeopathy and Holistic care of animals, as well as numerous articles published in many magazines and journals. Dr Mark Elliott BVSc VetMFHom MRCVS MLIHM PCH DSH RSHom is to be found here: https://chichester-vets.co.uk/